My primary visual memory of the moment: a pair of Converse sneakers: Bright white, at most a month old, dangling as if the person whose feet were in them had no care in the world.

I had just looked up from my notebook when I caught sight of those sneakers. I didn’t look up further, because I wasn’t quite sure what my eyes might suggest about my state of mind.

Our client, who was wearing the sneakers, had just asked two things, one of them quite general, the other quite specific, both of them having considerable consequences for the work we’d all done to date.

This was his general question: “I don’t want to say we’re going in the wrong direction, but what if we’re going in the wrong direction?”

This was his specific question: “Are we being a bit … condescending?”

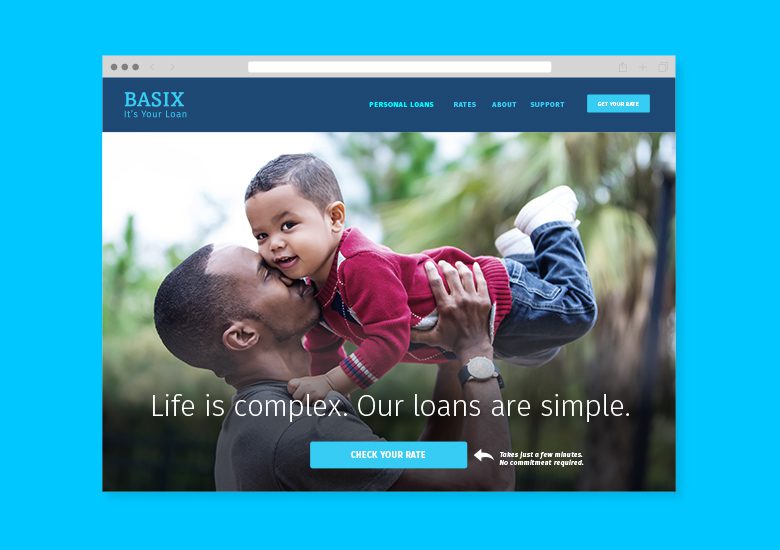

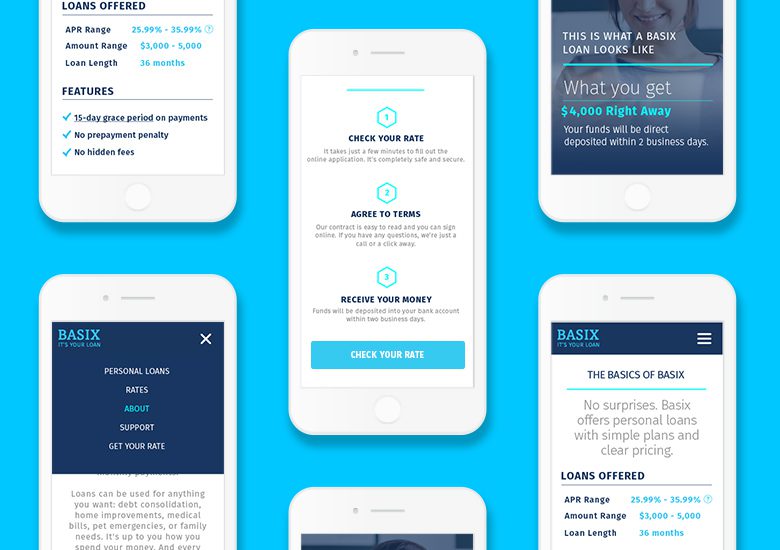

Let’s back up a bit. The project in question was Basix, a loan company developed by ZestFinance. The client was Kevin Morgan, then Zest’s Vice President of Marketing. Zest is a machine-learning company. That ubiquitous buzz phrase, machine learning, means that the folks at Zest teach computers not only to calculate but to self-improve. What Zest’s algorithms do is assess risk, and the risk assessment business happens to have a lot of applications in the financial industry, in particular for loans to consumers, and especially when those consumers are likely to be turned down for traditional loans. Basix was Zest channeling its enterprise product into a consumer product.

We’d worked on Zest for years, and on its Basix launch from the start. We actually named Basix while the service was still in development. That’s a great position to be in, but it’s a whole separate story from this. This story isn’t about naming. This is a story about doing a 180 midstream.

At the core of Basix was being friendly, approachable. We had worked up a name that had a little swagger, but suggested something well-founded: fundamental but not rudimentary. We had a nice blue color scheme, one that brought to mind the blue of a clear sky more than it did the color associated with blue chip stocks.

And when this momentous “Converse sneaker moment” occurred, our work on the Basix website language was essentially complete: polite instructions on how to apply, plain-stated information about the company, and handy suggestions about best practices for people looking to work their way out of bad financial circumstances.

You can’t go wrong being friendly, right?

Wrong.

Kevin had a point. The people who apply for loans, especially near-subprime loans, aren’t looking to make friends. Making friends isn’t even in the top 20 reasons why they’re applying for a loan. They are suffering hardship, they likely feel negative about themselves for their situation (that being the downside of the American myth of self-sufficiency), and they’re used to being denied loans. Worse: When they’re accepted for a loan, they’re used to feeling ripped off.

And here we were giving them little tips about savings accounts and priorities, interest rates and perseverance, like it’s that easy.

It isn’t that easy.

Time was tight. Launch was happening, whether or not we made good on the client’s sudden questions about the attitude our planned branding was projecting.

We went back to the source, research, and dug into it in two ways. First, we read up on the state of near-poverty in the United States, about what experts in the field think about the mindset and emotions of people seeking financial assistance. Second, we spoke with customers and, in a neutral manner, proposed various modes of describing the offering.

The research didn’t surprise us. We’d learned that people in bad financial situations experience stress in a manner that’s akin to the loss of a loved one, and that that’s exactly the emotional state in which one shouldn’t make big decisions. We’d pursued the “empowerment” path, but it led to a dead end of platitudes and fake smiles.

What, then, did it mean if Basix was never going to be seen as “friendly,” in the personal sense, by its customers? It meant we had to drastically revise our goals. Basix no longer wanted to be the best friend of its customers (which is what so many brands strive to be). Based on the fact that most potential loan customers apply to, and are rejected by, numerous loan companies, we set our bar much more realistically: We just wanted Basix to be the loan company that its prospective customers disliked the least. Those last three words — “disliked the least” — were very grounding, and everyone on the project took them to heart.

In the follow-up conversations with current and potential customers, we learned that this new approach — which we termed “non-judgmental” — registered strongly. Being “non-judgmental” turned out quite complex to pull off. You can’t prove a negative. The best you can do is avoid situations where in any way, positive or negative, you can be perceived to pass judgment.

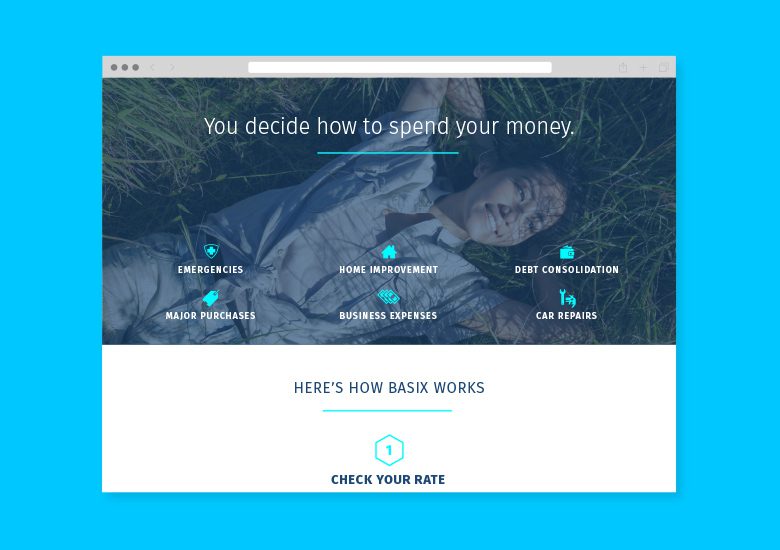

We summed this new mindset, this new brand point of view, in three simple words: “It’s your loan.” And we expanded that into expressions that were intended to show that the customers’ decision about what to do with their loan was entirely up to them: medicine, vacation, rent, car repair? It’s their loan, their decision.

Interview after interview, we heard from customers that no loan company had ever said such a thing to them. The idea that it was “their” loan was an entirely different way of perceiving the relationship between themselves and a loan company, but it was a solid one, devoid of empty promises and Pollyanna advice. We had successfully lost the condescension that Kevin had, at the last moment, sensed to be hanging in the air.

The fact is that Kevin, in his white sneakers during that fateful meeting, by no means had no cares in the world. Quite the contrary: He was in the process of launching not just a brand but a company, and one that its customers would quite literally depend on for their well-being. He wasn’t nervous, though, because he had sorted out the questions that needed to be answered, and he had the confidence that we could help answer them.